Thus, there is a sharp distinction seen between production (authored by directors in Japan) and consumption (inside vs. This produces a conception of transnationality whereby people consuming anime outside of Japan are consuming Japanese products, which is less transnational (across borders, operating beyond the received notions of nation-state) and more inter-national (two distinctive nation-states engaged in cultural exchange, Iwabuchi 2010), producing a sense of “inside-outside” that is relatively neatly defined-in this case, consuming Japanese media (produced inside of Japan) while the consumers are outside of Japan. When considered in the context of transnational consumption, we find the same methodological approaches common in analyzing anime as a commentary on Japanese society by directors: anime is “Japanese culture” consumed outside of Japan, making anime works a speech-act about Japan, because, as is commonly thought, anime comes from Japan. Rather, I want to highlight how this tendency of attribution to some singular agent reveals a tendency towards certain conceptions of authorial agency, creative and cultural production, and methodological approaches to interpreting (and consuming) anime. Here I do not mean to say that directors should not be given recognition, or that they are not involved in many levels of the production (for which Miyazaki is notorious). This allows for an analysis of the anime work in question as producing a commentary, a commentary that is often seen as addressed to Japan and read as focusing on the topic of Japanese society. In a sense, such an approach makes the film product become the director’s “speech-act”, so to speak.

Here “production” becomes less of a process as the focus switches to the “producer” as the central, authorial agent. In consideration of this, there is often an implicit understanding that there are other agents involved in the production, but researchers continue to utilize the singular director as a type of short-hand for an agent which orchestrates the major decisions of the production.

1 Such a concentration on film is reflected in the tendency to elevate these directors to the status of auteur, even though the problems of auteur theory from film criticism are widely acknowledged. A set of famous directors occupy the majority of the focus: Hayao Miyazaki, Mamoru Oshii, Satoshi Kon, and, more recently, Mamoru Hosoda and Makoto Shinkai. It is often a film that is taken up as the subject of inquiry, with the director the person the work is attributed to. The approach to anime as a media consumed transnationally is often one where the audience is seen as consuming “Japanese culture.” In academia (which is its own type of consumption-production), an extension of this is revealed in some analyses that focus on a particular work’s commentary on Japanese society. Lastly, I will examine how transnational sakuga-fans tend to focus on anime’s media-form as opposed to “Japaneseness”, practicing an alternative type of consumption that engages with a sense of dispersed agency and the labor involved in animation, even examining non-Japanese animators, and thus anime's multilayered transnationality. Anime production thus operates as a network of actors whose agency is dispersed across a chain of hierarchies, and though unacknowledged by Shirobako, often occurs transnationally, making attribution of a single actor as the agent who addresses Japan (or the world) difficult to sustain.

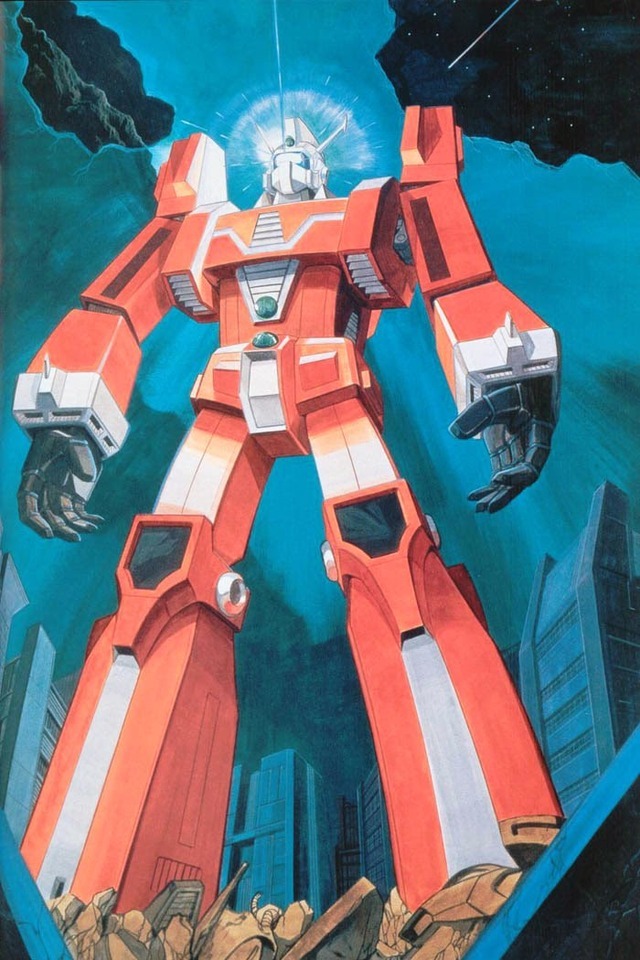

#Shirobako space runaway ideon series#

This will be done through an analysis of Shirobako (an anime about making anime), revealing how the series depicts anime production as a constant process of negotiation involving a large number of actors, each having tangible effects on the final product: human actors (directors, animators, and production assistants), the media-mix (publishing houses and manga authors), and the anime media-form itself. As an alternative reading of anime’s global consumption, this paper will explore the multiple layers of transnationality in anime: how the dispersal of agency in anime production extends to transnational production, and how these elements of anime’s transnationality are engaged with in the transnational consumption of anime.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)